“[Elizabeth Kemble] was a real professional, but more importantly, she was a person of genuine compassion. She cared about people, their health, their joys, and the pain of the spirit that sometimes surrounded her friends and loved ones. No one escaped her attention; no one failed to receive her active concern. She was busy with all humanity who moved about her regardless of the station in life.” –William C. Friday, former UNC system president (1956-1986)

In August 1950, Elizabeth L. Kemble took a road trip across North Carolina. She traveled nearly 600 miles from Murphy to Manteo, stopping at filling stations, professional offices, and stores along the way to chat with her new state neighbors. She wanted to know them, to understand their personalities and needs.

That’s what made the founding dean of the UNC School of Nursing such a powerful figure. She was passionate for people and truly cared about the individual — characteristics of not only a great leader but a dedicated nurse. “I took quite seriously that the boundaries of the university were the boundaries of the state,” she once told a reporter from the Winston-Salem Journal. “I felt we had an obligation to the people.”

_______

Before she came to North Carolina, Kemble spent years in the nursing profession. She earned her nursing diploma from the University of Cincinnati in 1927, followed by a bachelor’s from New York University in 1940. By 1948, she had both a master’s in nursing and doctorate in nursing education — accomplishments that were almost unheard of for a woman of her time. By 1950, she had held teaching positions in Ohio, New Jersey, and New York; was associate director of the Nurse Testing Division of the Psychological Corporation; and achieved national prominence as the director of the Department of Measurement and Guidance of the National League of Nursing Education.

Before she came to North Carolina, Kemble spent years in the nursing profession. She earned her nursing diploma from the University of Cincinnati in 1927, followed by a bachelor’s from New York University in 1940. By 1948, she had both a master’s in nursing and doctorate in nursing education — accomplishments that were almost unheard of for a woman of her time. By 1950, she had held teaching positions in Ohio, New Jersey, and New York; was associate director of the Nurse Testing Division of the Psychological Corporation; and achieved national prominence as the director of the Department of Measurement and Guidance of the National League of Nursing Education.

When it came time for UNC School of Medicine Dean Walter Reece Berryhill and his team of physicians to recruit applicants for the dean of nursing position, Kemble was a standout player. They knew she was an “exponent of the most progressive thinking in her profession, and that she had the background and experience to construct a curriculum and pick a staff to carry it out,” writes Gayle Lane Fitzgerald in her short history on the School of Nursing.

Beyond professionalism, Kemble brought a regimented but kind demeanor to the classroom. She once said: “There is no such thing as a menial task in caring for a human being.” And that’s what she did for her students. Upon recruiting the first-ever female freshman class for the new school, she interviewed each student personally — and she paid attention, making note of their individual needs.

“She was very welcoming and warm,” Bette L. Davis, one of the school’s first graduates of the four-year program, remembers from her entrance interview. “I was concerned about whether or not I would be admitted because some of my grades weren’t where they should have been my first few years of high school. But she stressed that everything would be taken into consideration, and I was accepted into the program.”

And when the first year of the master’s program had just one student enrolled because two dropped out, Kemble still provided a top-notch learning environment and education. “When we needed larger discussion groups she rallied the whole hospital from the administrator to the supervising nurses,” Audrey Booth, the School of Nursing’s first M.S. of Nursing Administration degree holder, says.

Kemble skillfully guided the nursing school down a difficult road filled with the familiar potholes of 1950s and ‘60s gender biases. Not only did she rally Dean Berryhill to give the program proper placement within its own school alongside big players like the School of Public Health and the School of Pharmacy, but she fought for funding for a proper building (Carrington Hall wouldn’t be erected until 1970). Additionally, she constantly encouraged her female students to persevere beyond the many hurdles that lead to dropouts such as marriage, a lack of role models, and personal fears of failure.

“The ethos of the UNC School of Nursing is one of pioneering, and you can draw a straight line to Elizabeth Kemble as the source of that ethos,” School of Nursing Dean Nena Peragallo Montano says. “Her vision and energy for this school at its founding made their way into our institutional character, and her fingerprints are on each of the many firsts for which we’re so well known. Her passion to bring better healthcare to the people of North Carolina is an inspiration to me, personally, and continues to guide the work we do here each day.”

A portrait of Dean Kemble — a gift inspired by the 1955 class — can be found on the second floor of Carrington Hall. They encountered a few roadblocks in procuring this piece of art. First they had to convince Dean Kemble and, secondly, they needed money for “the best oil painting” they could get. With $100, they started a fund at graduation that continued each year until, in 1961, at the School of Nursing’s 10-year anniversary, it was completed and gifted to Dean Kemble.

Building a bachelor’s program

In the fall of 1950, Kemble took on a seemingly impossible task. With a budget of just $2.25 million, she needed to hire faculty, develop a curriculum, oversee the construction of the School of Nursing building and dorms, find additional scholarship funding, and recruit high school seniors for entrance into the first-of-a-kind program, set to begin in fall of 1951.

The students she handpicked herself, but not without some hurdles. Some parents, for example, remained reluctant to let their adolescent daughters live on a college campus, but Kemble pushed forward. She sent letters to 737 North Carolina high school principals, spoke with groups of prospective students, and contacted newspapers and radio announcers around the state, stressing how the program was the first of its kind — an unprecedented opportunity for young women.

At the time, earning a bachelor’s degree in nursing was rare — and controversial. Many nurses received their education through diploma programs at their local hospitals. The rise of a four-year degree created an ever-widening education gap between the two kinds of programs. “We still have people today whose only education was a diploma program — and there’s continued discussion about it today as we close the gap,” Booth says.

Kemble recruited 27 bright-eyed women for her first freshman class — a big deal for a university that had, up until that point, only admitted women as transfer students. Kemble took pride in her new troop and went above and beyond to accommodate everyone’s needs, which earned her great respect from all who met her. “She was very involved with each one of us,” Davis says. “She really knew us. She made us feel that we were important and was strongly interested in helping us any way that she could.”

She led with endless support but also rigorous rules through strict curfews, closed study hours, and an arduous academic program. “She was a no-nonsense lady,” Booth says. “You didn’t approach her without having your facts straight” — an intensity that probably came from years of constantly defending the nursing profession.

Even before organizing UNC’s program, Kemble fought hard to make it its own school — rather than just a department within the medical school. “It was widely known that Dean Berryhill was eager to have the School of Nursing under Medicine,” Booth explains. “And Kemble was eager not to — she wanted it to be an independent school. She prevailed.” Davis adds: “I heard through the grapevine that she was given a hard time by the other schools within the Division of Health Affairs. She really had to fight her way through.”

By the fall of 1951, the nursing program was its own school, with four faculty members — including Kemble — and an excited, “history-making” freshman class. Dormitories and a proper building to house the school, though, would not be completed until 1953. Students spent their freshman year in Smith Dormitory on main campus, and their fall quarter sophomore year down the hall from the morgue on the fourth floor of North Carolina Memorial Hospital. The sound of gurneys wheeling bodies down the hallway woke the students on many occasions.

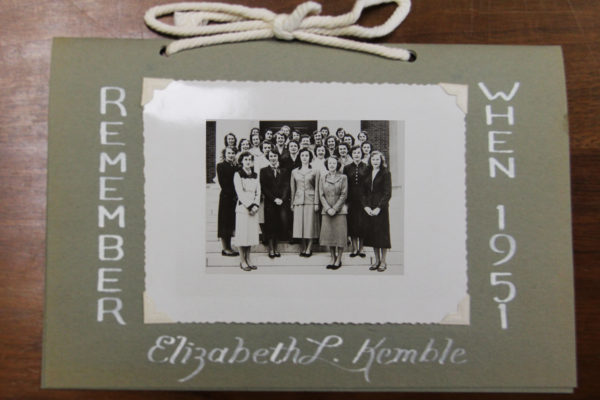

- Dean Kemble earned her nursing diploma in 1927 from the College of Nursing and Health at the University of Cincinnati. Most of her students had never seen her in a nursing uniform — the white cap, pin, shoes, and hose. Here, she stands among her class. “I can only imagine how she was before she was ‘The Dean,’ when she was Elizabeth Kemble, RN, on duty in a hospital somewhere in Ohio or New York wearing her crisp white uniform and nursing cap, interacting with and caring for patients, and setting the standard for excellence in professional nursing. The bar would be very high indeed,” Donna Blair Booe writes in “Ahead of Our Time,” a book of memoirs celebrating the class of 1955.

- Dean Kemble meets with the first applicant of the UNC School of Nursing in the spring of 1951.

- Dean Kemble (second from right) chats with students from the class of 1955. From the left, they are Sally Winn Nicholson, Rae Hylton Starnes, Pat Colvard Johnson, and Geri Snyder Laport.

- Dean Kemble shares a laugh at the School of Nursing dedication April 23-24, 1953. The new buildings were dedicated along with the Schools of Dentistry and Medicine, as well as North Carolina Memorial Hospital.

- Mrs. Spencer Love, a member of the School of Nursing Committee, held a special dinner for the 17 to-be graduates at her home on May 17, 1955. Although the first class began with 27 students freshman year, a handful left the program for various reasons. Those who completed the four-year degree are, starting from left to right with the top row, Martha Yount Cline, Virginia Edwards Coupe, Pat Colvard Johnson, Sara Blaylock Flynn, Winnie Williams Cotton; middle row, Louise Norwood Thomas, Joy Smith Burton, Mary Anderson Leggette, Janet Merritt Littlejohn, Sally Winn Nicholson, Gwen Huss Butler, Rae Hylton Starnes; bottom row, Bette Leon Davis, Geri Snider Laport, Gloria Huss Peele, Donna Blair Booe. Missing: Arlene Morgan Thurstone

- Upon graduation, that first class attended a special senior-faculty breakfast, which included a handmade program themed, “After Four Years Dreams Come True.” The program included space for autographs, so the class presented a special one to Dean Kemble, overflowing with sincere thoughts and fond, sometimes funny, memories. Donna Blair Booe wrote: “I think that all the times I’ve had to ‘see the dean’ about panty raids and such has been a greater part of education.” In return, Dean Kemble gave each student a handwritten note.

- Dean Kemble (second from left) drinks tea with members of a graduating class from the late 1950s.

- Throughout her time as dean, Kemble constantly made headlines in local newspapers. She was even publicly praised by former North Carolina Governor Terry Sanford at the school’s 10-year anniversary. “Every North Carolinian can find cause for pride in what has been achieved here and, even more important, in the wonderful contribution the school has made,” he stated at the celebration.

Changing the nursing profession beyond UNC

For the next 10 years, Kemble would face a slew of other challenges both big and small. She continually discussed the need for scholarships and successfully solicited hundreds of thousands of dollars from both federal and private sources. She also pushed to get the hospital’s machine shop moved out of the nurses’ dorm.

“[Dean Kemble] was in a battle for the life of the school,” writes Fitzgerald. “Each encroachment from the School of Medicine and the hospital were further indications to her of the continuing efforts by some members of the medical community to swallow up the School of Nursing and reduce it to a diploma program administered by the hospital.”

By the time the school celebrated its 10-year anniversary, Kemble had secured accreditation for the bachelor’s program (1955) — the first nursing school in the state to do so — as well as the master’s program (1961), which began in 1955. Enrollment increased from the initial 27 students to a solid 235. But as Kemble so aptly stressed in her speech at the decade’s celebration, “Much has been accomplished. Much remains to be done.”

Regardless, her years of experience in nursing education and administration caught the eye of the United States Air Force, who brought her on as the national consultant to the Surgeon General in 1959. She became the first professional nurse to be ranked a brigadier general and, in 1962, spent one month traveling the world. Bases in Germany, Spain, Turkey, France, and Libya hosted her as she gave detailed presentations on trends in nursing education, service, research, and the changing role of the nurse.

When she wasn’t traveling the world, or attending a board meeting — she served on more than 10 boards including the National Institute of Mental Health, American Nurses Association, and the first editorial board of the journal Nursing Research — Kemble could be found relaxing just outside of Chapel Hill at the 68-acre farm she shared with her longtime friend Thelma Brummett. On a few occasions, she invited her students over for dinner and she’d transform into the lighthearted hostess.

“This was a side of her we rarely had the privilege of seeing: casually dressed in her slacks and sweater, in a lounge chair, happily smiling with twinkling eyes as we exchanged the impromptu dialogue concerning our current issues, whether academic or social,” Janet Merritt Littlejohn, another alumnus from the 1955 class, recalls. “She listened intently and related on a personal level. This was such a pleasant memory for us.”

“She had a great sense of humor,” Booth adds. This side of Kemble especially revealed itself at the 10-year alumni reunion, where she reflected on the “panty raid” that took place when the first freshman nurses arrived; the nursing faculty’s concerns that the wheeling of corpses past the girls’ rooms when they lived in the hospital would “warp [their] young personalities”; how the 1957 class “wanted to specialize in chemistry, so they took it three times”; and the need for Saturday classes for the 1960 graduates because they couldn’t stay awake in summer school.

More than anything, Kemble has been remembered for her perseverance and long list of achieved goals that have molded the School of Nursing into the top-notch institution it is today. “I didn’t realize, for a long time, the significance of what Dean Kemble set up at UNC for the state of North Carolina,” Davis admits. “All the details that came to be are because of her. And then she was very instructive in helping us find our own goals as a nurse and the goals of nursing as a profession — so much of which she taught during our senior seminar with her.”

From 1950 to her retirement in 1968, Kemble continued to put people first. “We knew she cared for all of us, individually,” Davis adds. “We loved her, and I think we were very lucky to know her.”