A man in Phoenix, Arizona, calls his mother in Columbia, South Carolina, every Sunday at 6 p.m. — a 20-year-old ritual as sacred for them as Sunday morning church service. For two decades she never failed to answer her phone. On a Sunday just before Halloween in 1999, her phone rings and rings and rings. No answer.

A few days later, in South Carolina, EMT Sean Kaye responds to a strange call from the local emergency medical services dispatch center. “They told us not to use our lights or sirens,” the paramedic explains. “Well, we always use our lights and sirens, so we found this really bizarre.” He and his partner arrive at a house built in the 1960s. They sit and wait.

A few days later, in South Carolina, EMT Sean Kaye responds to a strange call from the local emergency medical services dispatch center. “They told us not to use our lights or sirens,” the paramedic explains. “Well, we always use our lights and sirens, so we found this really bizarre.” He and his partner arrive at a house built in the 1960s. They sit and wait.

Ten minutes later, a cab pulls up to the curb and a 50-something man gets out of the car. He explains the weekly phone calls, her medical problems, her heart condition — and that he doesn’t have a key to her house. This is not an issue for someone like Kaye, an experienced EMT who’s been locked out of homes before. He kicks down the door. Entering the dark house, he feels around like he’s blind-folded, trying to get his bearings. Upon reaching the back bedroom, he finds the man’s mother in her bed.

“The man felt so guilty because his mom lived by herself,” Kaye remembers. “They talked every weekend for 20 years — 20 years. I felt for him. It takes a toll on you, hearing a story like that.”

————–

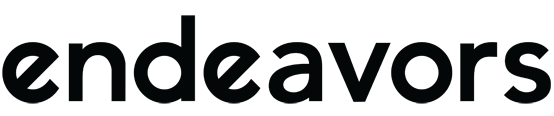

In North Carolina alone, approximately 32 people die each day from out of hospital sudden unexpected death (OHSUD). The narrative above is not uncommon, and the family and friends left behind are almost always emotionally overwhelmed. In the United States, OHSUD accounts for approximately 15 percent of all natural deaths according to UNC’s SUDDEN Project. Founded in 2012, the study is dedicated to surveillance and prevention.

Since the project’s start, the SUDDEN team has identified five medical conditions that lead to sudden death in North Carolina, four of which deal directly with the heart: high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, coronary heart disease, and cardiomyopathy — a hereditary disease of the heart muscle that makes it difficult for the heart to deliver blood to the body.

“In the search for victims of sudden death, previous studies looked for people who died unexpectedly but with witnesses,” Paul Mounsey, a co-principal investigator (PI) for the study and UNC cardiologist, says. “There are a lot of other people out there, though — socially isolated people who live alone — who have the same mechanism of death, but with no one to report it.”

For the study, Mounsey, UNC cardiologist Ross Simpson, Director of Cardiac Electrophysiology Research Irion “Chip” Pursell, and their team analyzed all deaths in Wake County for the population between 18 and 64 years of age. “In doing that, we’ve established that the incidence of unexpected death is much higher than people thought it was — at least in Wake County,” Mounsey explains. “It’s a much bigger problem than anyone ever thought.”

Sifting through the data

Computers equipped to electronically filter death certificates help SUDDEN researchers determine potential cases that could be characterized as OHSUD. The software collects data by county and calendar year, and filter information by age, location of death, and manner of death. Deaths due to cancer and drug overdoses are not included. Clinical data is abstracted from the subject’s medical records to inform prevention efforts.

What is sudden unexpected death?

A malfunction of the heart that results in a rapid loss of blood flow through the body, leading to death. It happens immediately and may have few or no known warning signs.

The SUDDEN team hopes to, ultimately, identify risk factors for OHSUD so they can initiate prevention strategies in high-risk communities. In truth, sudden unexpected death affects all of us. It’s similar to suicide, in that most of us know someone who’s passed suddenly. People who live in poverty, though, are affected more, according to Mounsey. Using data from the U.S. Census, he and his team have demonstrated that people with the lowest household income are much more likely to die suddenly. Habitual drug users who don’t overdose, as well as people with mental health problems also have an increased risk of passing unexpectedly.

For OHSUD victims with access to health care, many abstained from taking their doctor-prescribed, preventative medications. “This was a surprise to us,” Mounsey says. “Especially with people who had medical records. With those cases, we knew if they had high blood pressure or coronary artery disease or whatnot — and they weren’t always taking the recommended medications to prevent something like this from happening.” Approximately 50 percent of the OHSUD population passed because they didn’t take their prescriptions, according to Mounsey.

“We’ve been collecting data for a year or two now, but we need so much more to prevent sudden death victims from dying,” Jason Stopyra says. The medical director of emergency services in both Randolph and Surry counties, Stopyra leads the intervention and prevention components of the project in those areas. Most recently, he and his team of paramedics attempted to reach the recently deceased as close to their time of death as possible to perform echocardiograms — a test that uses ultrasound waves to produce a visual display of the heart.

“This had never been done successfully anywhere in the world until we did it,” he says. “One of the biggest problems with echocardiography is that most ultrasounds are done after the patient has been deceased for more than six hours. We were able to do the ultrasounds almost immediately. That allowed us to get images we could actually use.”

Like a star chart for an astronomer, an echocardiogram is a map of the heart for the cardiologist — it tells the story of a heart’s activities. Up until this point, cause of death on most death certificates of OHSUD victims are just best guesses, according to Stopyra. “They are not rooted in any fact,” he says. “It’s just what the medical examiner or treating physician thinks the cause of death is. An echocardiogram solves that problem.”

Prevention through collaboration

SUDDEN study researchers have teamed up with emergency service groups in Wake, Surry, Randolph, and Orange counties, as well as epidemiologists at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. “Epidemiologists understand how to take very diffuse data you get from looking at patient records and then make scientific deductions from it,” Mounsey says. Carolina Demography is also helping to identify which populations the team should study.

The group has a collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency, too. “It has been known for a long time that periods of high atmospheric pollution are periods when people die suddenly,” Mounsey points out. London’s Great Smog of 1952, for example, killed 4,000 people and made 100,000 more ill. The catastrophe occurred when a period of cold weather and windless conditions combined with pollutants created from burning coal to form a thick, seeping layer of smog that swept across the city. It lasted for four days and led to the Clean Air Act of 1956.

People at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) hope to use the study’s results to improve coding on death certificates. “If you find someone on the floor, fully clothed, what do you write on the death certificate?” Mounsey asks. “The CDC is concerned that the coding for certificates isn’t as accurate as it should be.”

Technological advancements

Today, the SUDDEN team analyzes death certificates in North Carolina and plan to expand to South Carolina and Georgia. As electronic medical records continue to grow, they hope study more places across the United States and eventually automate the analysis process. “If we can provide states with an automated method to pull death certificates and query medical records electronically, we can show them where the hot spots are for unexpected death and who in their population is vulnerable,” Mounsey explains.

Technology has already saved countless people who live alone. “There are fewer people dying alone in their homes today thanks to cell phones,” Kaye points out. “But EMTs still get calls probably twice a week to report to a scene where someone has died. And while technology has changed, it’s still hard on the family.”

That’s why Mounsey feels he and his team need to continue to push the message of good primary care out into the population. “How do you deliver this message to the people who need to hear it?” he asks. In Surry County, they’ve developed a prevention task force comprised of the county health director, hospital case managers, community health workers, emergency services staff, and veteran service organizations. “We want to figure out how we can work together to identify gaps in care and prevent sudden death across the county,” Pursell says.

“There’s still so much we don’t understand about it,” adds Stopyra, who has spent 23 years in emergency services and 16 as a practicing physician. “It’s a real epidemic in the world today. If we can figure out a way to identify those at-risk and then prevent it, I think we’ve done a great service to not only the health of the community but the morale of the medical community and public as a whole.”