The year is 2012. Keely Muscatell sits on a slipcovered couch in her dingy L.A. apartment. A PhD student at UCLA, she opens her laptop to check her email and scrolls through her inbox until she finds what she’s looking for — the results of a psychology experiment that would make or break her dissertation. Her cheeks grow warm, her heart quickens, and she sucks in her breath.

This moment isn’t all that different from the experiences she’s studying: how social stressors show up physically in the body. More specifically, she wants to know if negative social experiences lead to an increase in inflammation.

Spoiler alert: They do.

The data clearly showed that participants’ inflammation increased over the course of the study session — a discovery that would allow Muscatell to continue her research on this topic.

Fast-forward to 2022, and Muscatell runs her own lab at UNC-Chapel Hill. As a professor in the psychology and neuroscience department, she continues to study how psychological experiences influence what happens in the immune system, a field called psychoneuroimmunology.

“Social experiences and physiology are clearly interconnected — just ask anyone if they’ve felt their heart pounding before an important presentation or felt butterflies in their stomach in anticipation of a first date,” she shares.

Muscatell wants to understand how the body responds to psychological stress from social experiences, like racial discrimination, poverty, and loneliness — and she’s one of the few scholars in the field researching this topic.

Her work has been recognized by big names in the research world. In 2021, she received an NSF CAREER Award — a competitive five-year funding mechanism for early career faculty — to continue this work. In January 2022, she was awarded the American Psychological Association Distinguished Scientific Award for Early Career Contribution to Psychology.

She credits the success of her lab, and her cutting-edge research on racism, to her graduate students.

“I feel almost like the CEO of a small business, where my job is to raise the money for the ideas,” she shares. “It’s really the rest of the lab that moves things forward, and I’m just kind of a traffic director. In some ways, I am just trying to get out of their way.”

Muscatell’s interest in racism-related stressors, in particular, stems from two PhD students: Carrington Merritt and Gabriella Alvarez. Both joined her lab in 2018.

Using neuroimaging, Merritt researches how experiences of discrimination impact mental and physical health and lead to the onset of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Alvarez explores how our environment shapes our physical health and mental well-being and has studied this in people from different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

“This isn’t a case of the brilliant person thinking their thoughts in an office and writing them down,” Muscatell shares. “My lab is a team. We actually use the language ‘family.’ We’re a family. We’re here to work together and help each other. That’s how we’re going to lead to the biggest breakthroughs — by working together. And I hope that pulls in a new generation of people who might have been left behind by science in the past.”

Finding her field

Muscatell first learned about the field of psychoneuroimmunology in the place where the term “psychoimmunology” was coined: the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). In 1964, UCLA researcher George Solomon and his team published a landmark paper on how stress, emotions, immune function, and disease are connected. Specifically, they studied how emotions affect the progression of rheumatoid arthritis.

“I think prior to the founding of this field, most people thought the immune system and the brain were these separate processes, that there was no way for them to talk to each other,” Muscatell says. “So the immune system was sort of from the neck down, and it just came online when it needed to deal with a problem.”

UCLA is home to the Norman Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology, and Muscatell’s mentor there, Naomi Eisenberger, was doing “some really pioneering work” in the field, investigating the links between social cognition and rejection, the brain, and the immune system. Her discovery that the brain processes social pain similarly to the way it manages physical pain was recognized by the American Psychological Association, which gave her its Award for Distinguished Scientific Early Career Contributions to Psychology — the same award Muscatell received earlier this year — in 2013.

“I just thought it was so fascinating that, on the surface, these psychological experiences seem to have nothing to do with the immune system and yet they do lead to changes happening in our bodies,” Muscatell says.

Muscatell’s experience at UCLA was also the first time in her life where she began to experience imposter syndrome. Until that point, she had attended public schools her whole life, including the University of Oregon for her bachelor’s degree. At UCLA, she found herself surrounded by peers from elite institutions like Harvard, Stanford, and Yale.

“I didn’t know if I could make it given where I had come from,” she says. “That had me thinking a lot about social hierarchies and the way in which those hierarchies influence people’s functioning and well-being.”

In a study for her dissertation project, Muscatell used blood samples and MRI scans to observe inflammation in the body after a stressful event as it relates to social status. Participants from lower socioeconomic backgrounds experienced more inflammation and brain activity in response to negative feedback. While Muscatell recognizes that socioeconomic health disparities are a multifaceted problem, this study suggested that there’s a psychological component to feeling devalued in society that could lead to poor mental and physical health over time.

“That was one finding that I thought was really interesting and intriguing in terms of understanding how these macro-level societal factors can influence the way that we respond to stress — both in terms of the brain and the body,” she says. “That’s one area of research that we’ve been following up on now that has led to our interest in racial disparities.”

Learning from social crises

In May 2020, as the nation watched an officer kneel on the neck of George Floyd, Gabriella Alvarez was reminded of a similar event that occurred six years earlier. While walking down the middle of a two-lane street in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, Michael Brown and Dorian Johnson were advised to use the sidewalk by a passing police officer. The exchange resulted in the death of Brown, who was unarmed and shot six times. In the days following, a series of riots broke out across Ferguson.

At this time, a 20-year-old Alvarez, who identifies as Afro-Latina, was a senior at Washington University in St. Louis — just 15 minutes away from where Brown was shot.

“This conversation about race in America was happening as I was coming of age,” says Alvarez. “It was then, and through my coursework, that I better understood structural inequities and how society can put individuals’ health at risk or harm them. This differed from other narratives I heard growing up, that some people are genetically prone or solely responsible for their health and well-being.”

With other students from Washington University, Alvarez visited the location where Brown was shot to protest the state-sanctioned violence that had occurred there. While standing outside the Ferguson Fire Department, she watched Brown’s mother and stepfather break down emotionally when it was announced that the officer would not be indicted for the killing. The crowd erupted in anger.

“I think experiencing that opened my eyes to how injustice actually works and highlighted how powerless we were to the systems in place,” she says. “Maybe the ‘good guys’ don’t always prevail at the end — that was a painful realization for me at the time.”

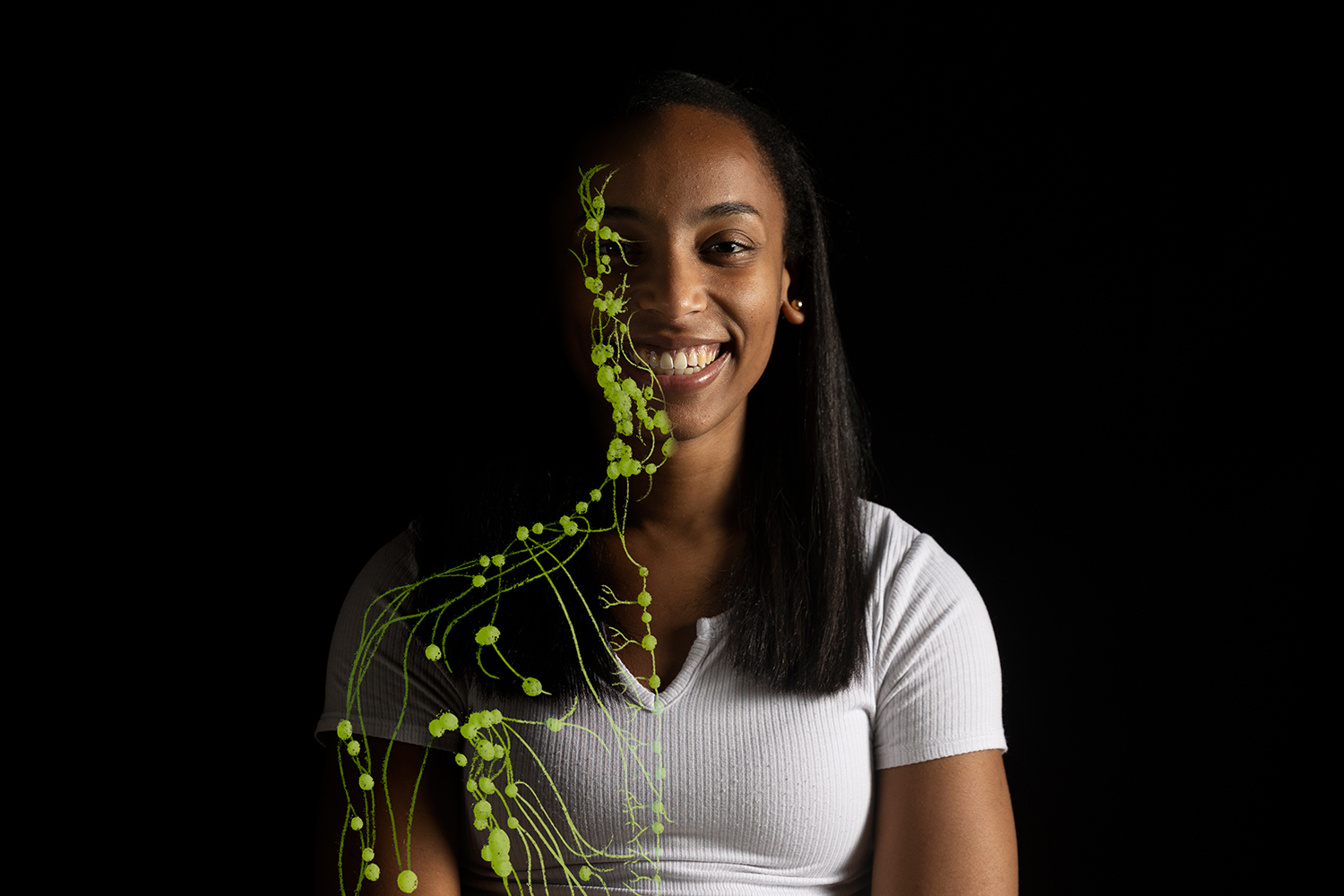

The nervous system communicates with the immune system, and vice versa, regularly – and the field of psychoneuroimmunology investigates these interactions. Within Muscatell’s lab, PhD student Gabriella Alvarez studies how environmental factors, like unemployment, adversity, and discrimination, affect these systems. (photo by Alyssa LaFaro; illustration by Corina Cudebec)

Alvarez, a psychology and anthropology double-major, seriously began to question why some people’s health and wellbeing are affected by society and the role race plays.

Now, as a PhD student in Muscatell’s lab, Alvarez studies this relationship in a variety of ways. One project uses MRI scans to observe the brains of people who are experiencing long-term unemployment to understand how chronic stress affects health. For another, she’s researching how early-life adversity affects the emotion regulation of teenage girls with a high risk of depression and other psychological conditions.

A third study looks at how prior experiences of racial discrimination influence the brain’s response to stimuli in the environment. Alvarez is also working on a project on how emotions shift as people age and whether early-life adversity impacts the way people process positive emotions over time.

When I point out that’s a lot of projects, Alvarez laughs and nods.

“My guiding question is: How does the environment change our brain and body?” she says. “What’s exciting about psychology is that it gives me the tools to ask these nitty-gritty biological questions about the immune system, collect blood, and analyze those markers, while also being able to consider the larger context of people’s experiences and how people understand their world.”

Striving to help others

While Alvarez was protesting the killing of Michael Brown in St. Louis, nearly 800 miles away, Carrington Merritt was starting her first year of college as a psychology major at UNC-Chapel Hill. In 2016, she joined the lab of David Penn and began studying schizophrenia. She soon discovered some startling statistics: Black people are twice as likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder than their white counterparts. Once diagnosed, they are more likely to be homeless, unemployed, and involved with the justice system.

The same semester, Merritt was also taking a class with Muscatell on how social stress impacts neural activity. She recalls learning about one particular study where participants were purposefully excluded from playing a game and were led to believe the exclusion occurred because of racial discrimination. Not all of the participants perceived the events in this way, but those who did feel discriminated against exhibited a different pattern of neural activity than those who attributed the exclusion to something else.

Working with both Penn and Muscatell inspired Merritt to study how experiences of discrimination impact mental and physical health and contribute to the onset and course of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Part of the immune system, lymph nodes communicate with the brain to fight infection and disease. Carrington Merritt, a fifth-year PhD student, studies how racism-related stress impacts Black individuals with schizophrenia. (photo by Alyssa LaFaro; illustration by Corina Cudebec)

“The fact that we are seeing such high rates of Black individuals – particularly Black men – being diagnosed with schizophrenia raises the question of whether there are unique social stressors these people are undergoing that predispose them to being more likely to develop this disorder,” Merritt says. “There’s this possibility that the effects of dealing with the stressors related to racism contribute to the onset of serious mental illness.”

Today, Merritt is a PhD student in Muscatell and Penn’s labs and is pursuing both the clinical and social psychology tracks in her department. Under Muscatell’s guidance, she researches the impact that racism-related stress has on the onset of schizophrenia, using both physiology and neuroimaging to do so. In Penn’s lab, she interviews Black clients seeking treatment for their psychotic disorders, asking them questions about how they feel their race impacts access to services or their ability to engage with their therapist. She hopes to adapt current treatment models to better serve Black clients.

“It’s exciting to me to study schizophrenia in all these different ways — both looking at how the brain responds to racism and the actual lived experiences of the people I’m trying to help,” she says. “For persons of color seeking treatment, I think it is rare to have people ask them how race or racism impacts them and how that impacts their mental health. Knowing this kind of research can bring that more into the conversation is important to me.”

Creating a safe space

Merritt credits Muscatell as the impetus behind her enrolling in both the clinical and social psychology programs at UNC. In fact, to help Merritt further study racism-related stressors in schizophrenia, Muscatell offered to co-write a grant with her that was only available to early-career faculty — and they got it.

“She really went out of her way to make this opportunity possible for me; it’s not something a graduate student could apply for,” Merritt says. “She doesn’t really do schizophrenia research outside of the fact that she has me as a graduate student who’s interested in the topic.

“One thing that’s unique about Keely,” Merritt adds, “is that she’s such a dedicated mentor and makes that a primary goal of hers for both undergraduate and graduate students, which I think in practice is hard to do. I’m saying this as a grad student trying to manage a few undergraduate research assistants on the studies I’m running. It’s hard, so it’s impressive that she’s able to do it effectively.”

Alvarez shares Merritt’s sentiments and stresses that Muscatell often goes above and beyond — not only to support her students’ research goals but their emotional and mental health.

“Through the pandemic and following the death of George Floyd, Keely was so supportive and willing to help the students of color in the lab who might be going through an especially difficult time,” Alvarez shares. “She reached out to offer extra research support, mailed little gifts, and let me know that she truly cared. During this challenging time, Keely reminded me that I belonged here. She doesn’t just talk the talk. She’s really risen to calls of equity and antiracism in our lab and department.”

Muscatell has been so inspired by Merritt and Alvarez’s work that studying stress and race has become a permanent part of her lab. Not only is she incorporating racism-related stressors in her own work, but her newest PhD students are also studying racism within the field of psychoneuroimmunology. Maurryce “Mo” Starks researches how vicarious racism — racism that is witnessed rather than experienced — shapes cognitive performance, brain activity, and immune responses. Megan Cardenas studies how environments laced with racism impact health.

For her own research, Muscatell will use her NSF CAREER Award to continue studying the links between social and immunological processes, and to improve the tools for measuring and manipulating the immune system so that this research is more accessible to others in the field. One of these methods involves using flu vaccines to induce a mild inflammatory response to understand how even slight bouts of inflammation affect our social behavior.

And, of course, another goal for this award is “to mentor and teach a new, more diverse generation of social psychoneuroimmunology researchers.”

“There’s this common term in psychology that research is me-search,” Muscatell says. “You’re trying to understand your own life experiences and the people in your family and your community. That’s been such a huge part of building a lab at UNC with my graduate students. Just seeing them and the questions they come up with based on their own life experiences — which are, most of the time, different from mine — is phenomenal.”