Charlene Regester has been an avid patron of University Libraries since she was a PhD student. In fact, she was one of the first students to get to use the Walter Royal Davis Library — lovingly referred to as simply “Davis” by students and faculty today — which opened on February 6, 1984.

“Most people don’t realize I’ve been parked in Davis Library ever since I was a graduate student,” says Regester, now an associate professor in the Department of African, African American, and Diaspora Studies and acting director of the Institute for African American Research at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Back then, Regester was studying African American film history. Because she wasn’t located near major entertainment cities, like New York City and Los Angeles, she felt her next best option was to collect and read Black newspapers from those places. She spent hours in the basement of Davis flipping through them on microfilm readers. When she needed newspapers they didn’t have, she worked with staff to order them and eventually collected more than 30,000 articles.

Today, Davis Library is one of the largest research facilities in the Southeast.

“Davis’ creation, to me, was the university doubling down on the assertion that you can’t be a great university without a great library,” says Elaine L. Westbrooks, vice provost for University Libraries and university librarian.

While Davis Library is the largest on campus, it’s far from the first. After Carolina’s creation in 1792, three libraries supported the work of students: the University Library and two others managed by the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies. The first library dedicated to research — Carnegie Library (now Hill Hall) — wouldn’t open until 1907.

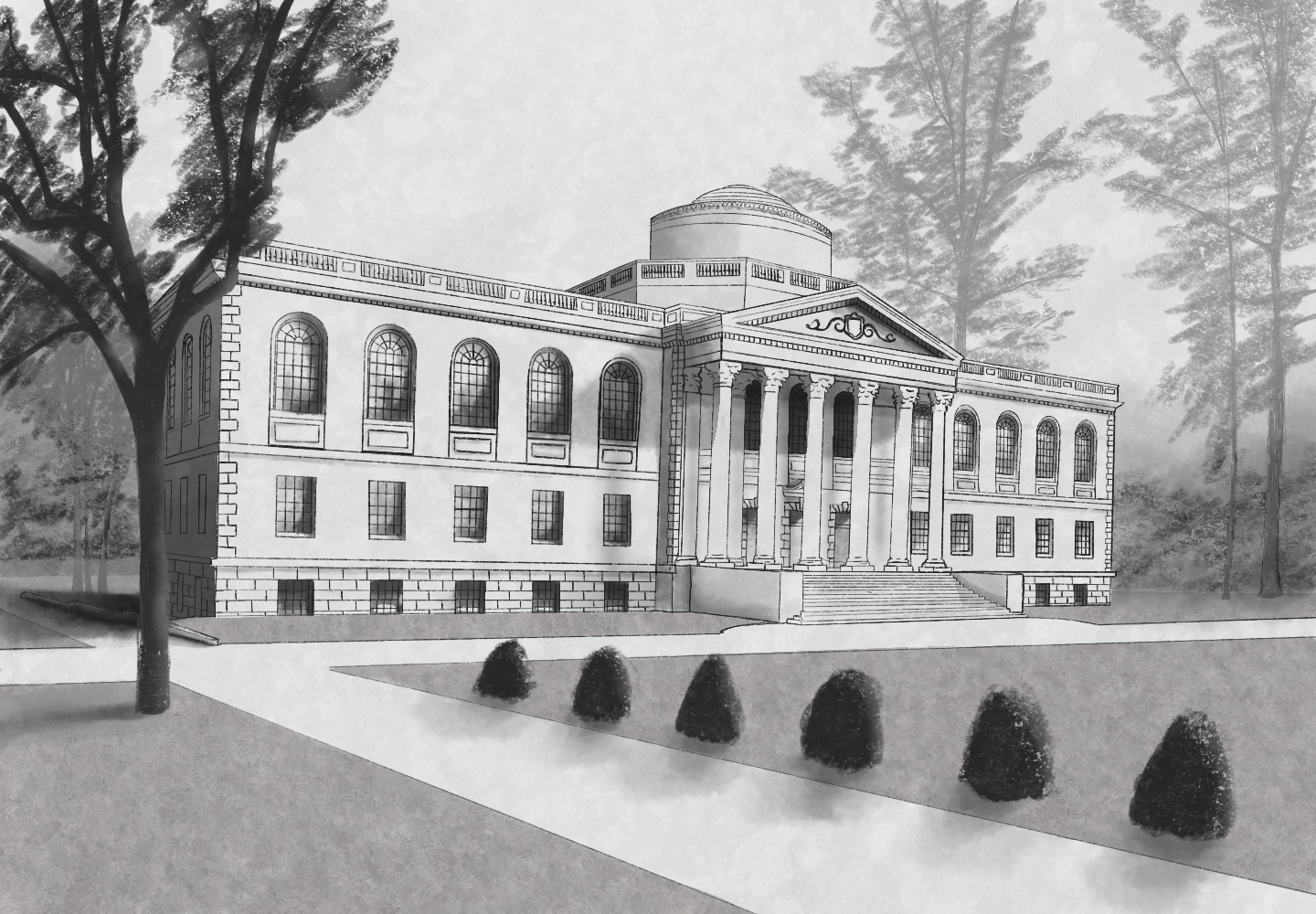

In just 16 years, Carnegie gained so many books that even the basement was filled with boxes stacked on top of one another. It was time to build a bigger, pan-campus library that could serve a rapidly expanding student body — an effort spearheaded by former UNC Chancellor Harry Chase, who oversaw the erection of Louis Round Wilson Library In 1929.

Completed in 1929, Louis Round Wilson Library was UNC-Chapel Hill’s first pan-campus library and sits at the heart of campus by Polk Place. This depiction shows what the library looked like upon its completion. (illustration by Corina Cudebec)

“Chase wanted to position UNC-Chapel Hill as a research university,” Westbrooks says. “And he knew he couldn’t do that without a library.”

Wilson Library is the place to study the American South and draws hundreds of researchers from across the nation and the world to North Carolina each year. It is home to five signature collections: the North Carolina Collection, the Rare Book Collection, the Southern Folklife Collection, the Southern Historical Collection, and the University Archives and Records Management Services.

Wilson and Davis are just two of numerous libraries at Carolina. Others specialize in a variety of topics, including law, music, health sciences, and art.

“A researcher is not going to go out and make new discoveries until they understand what has already been discovered,” Westbrooks says. “The libraries are tremendously important because they provide access to knowledge that has been created by other researchers — and building on that knowledge is what research is.”

That knowledge comes in many forms, not just books. Carolina’s libraries contain audiovisual materials like films and music, furniture, manuscripts, printing blocks, cuneiform tablets, and a massive digital repository. Students, faculty, and staff can rent equipment — like cameras, microphones, and projectors — at the Media & Design Center in the Undergraduate Library and have access to thousands of journals and databases thanks to dedicated efforts to obtain and maintain subscriptions.

“Libraries are about the future — not just a record of the past,” Westbrooks stresses. “We’re a place people love to go because of the possibilities. Whether you talk to a 4-year-old or an 84-year-old, everybody understands that libraries are fundamentally great places to build knowledge and discover new things. And that’s what we help people do in the research setting: Make discoveries, push the frontiers of knowledge, and solve the problems of the world.”

To showcase the breadth and depth of University Libraries, six researchers working within five different libraries have shared their projects with Endeavors.

Preserving Black Film History at the Media & Design Center

Charlene Regester continues to study the history of Black cinema before 1950. Most films made by African Americans before this time period are hard to find, Regester points out.

“I think either through neglect or lack of interest or not understanding the value, these resources have escaped us,” she says. “Some films have been found in people’s attics or garages — and they had no idea the value of those films.”

Much of her research has explored the works of Oscar Micheaux, an early 20th-century American author, film director, and producer who made upwards of 40 films. One that has drawn the attention of multiple scholars is “Within Our Gates,” which was found in an archive in Madrid, Spain.

“The film was very controversial because it might be one of the few records of a lynching that’s visualized on screen,” Regester explains.

Charlene Regester, associate professor of African, African American, and diaspora studies and director of the Institute for African American Research, in the Media & Design Center at the House Undergraduate Library (photo by Andrew Russell)

After Regester learned that the U.S. Library of Congress had obtained the film and translated it back to English, she hoped to get her hands on a DVD version to show in her classes. Staff members at the Media & Design Center within the R.B. House Undergraduate Library were instrumental in this process and have since found multiple Micheaux films for Regester to use in both her research and her courses.

Regester has also utilized Davis Library extensively. Librarians have helped her obtain film censorship records from the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, paper collections on Black actors and filmmakers, and microfilms of African American newspapers, like the Chicago Defender and New York Amsterdam News.

“I’ve learned over the years that your research is only as good as the resources you have access to,” she says. “Having access to these materials has opened up a whole realm of opportunity to revisit the past and document it. I hope I have advanced the field because of my own interest in recovering and researching these films, getting a sense for how African American filmmakers had to make films without appropriate budgets or technological inventions. I’m trying to fill that void in history.”

Unearthing Dead Languages in Wilson Library’s Rare Book Collection

Nanduq ershu subat balti nu’u ulap dame labish. That’s Akkadian for a Babylonian proverb: “The wise man is girded with a festive garment; the fool is clad with a loin-cloth.”

Akkadian is one of the earliest languages known to human history, spoken alongside the even older Sumerian language by the people of Mesopotamia — what’s known today as modern Iraq and the surrounding region — between 2600 and 500 B.C. While it is considered a dead language, specialists like religious studies professor Joseph Lam study and teach it.

In 2019, while teaching Akkadian to one of his classes, Lam remembered reading somewhere that the Rare Book Collection at Wilson Library had a few cuneiform tablets. Similar to hieroglyphs, cuneiform is the writing system used for both Akkadian and Sumerian and was often transcribed onto small, clay slabs the size of a modern e-reader. He worked with librarian Emily Kader to locate the tablets and found more than he expected.

“It was a little bit of a rabbit hole,” he says, chuckling. “When I got the list of tablets the library had, I found some that had never been published.”

Joseph Lam, associate professor of religious studies, in the Fearrington Reading Room at Wilson Library (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

One is an administrative record noting the number of workers employed at a millhouse on one particular day around 2000 B.C.; another is a letter documenting merchant dealings and activities.

“Think about what would survive from an average office in modern times,” Lam says. “It’d be mostly receipts and things like that.”

The collection also includes a cone-shaped artifact containing a royal inscription and cylindrical seals used to impress a signature onto a document.

This nearly 4,000-year-old cuneiform tablet details the number of workers employed at a millhouse. (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

Using 20th-century records about the purchase of these artifacts, Lam tried to track down their origins — and without much luck. The next best option, he felt, was publishing them so that other scholars could study them. But photographing cuneiform tablets is no easy task. Three-dimensional and covered in symbols, they need to be observed with specific lighting and at multiple angles.

Kader connected Lam with Jay Mangum from University Libraries’ Digital Production Center and Rebecca Smyrl, an assistant conservator at Wilson. Under Lam’s direction, Mangum photographed the tablets using custom supports built by Smyrl.

“We have an amazing library staff,” Lam says. “They’re not only knowledgeable, but they are committed to supporting the work of this university. At any point when I had a question or needed help, they always came through.”

Compiling Jim Crow Laws with Digital Research Services

When a high school social studies teacher asked UNC librarian Sarah Carrier for a comprehensive list of North Carolina’s Jim Crow laws in 2017, Carrier didn’t feel like she had the best answer: “States’ Laws on Race and Color” by Pauli Murray, published in 1951. This left out years of potential legislation — and manually searching through decades of volumes of N.C. General Statutes was no small task. But Carrier really wanted to help this teacher and others who might ask for this information in the future.

Carrier knew an automated solution was needed, so she worked with her library colleagues in Digital Research Services to find one. Enter Amanda Henley, head of Digital Research Services, who engaged more than 30 people — including librarians, library staff, postdoctoral researcher Kimber Thomas, and history professor William Sturkey — in a multi-year project using text mining and machine learning to identify racist language in legal documents. To date, they’ve discovered nearly 2,000 Jim Crow laws in North Carolina.

“I think the collaborative nature of this project is one of the reasons why the University Libraries is a good home for it,” says Henley, principal investigator on the project. “Because of where we sit on campus, we know what other people are doing and who has different areas of expertise. We also have a broad range of expertise within the libraries. That’s what allowed us to be so successful.”

Amanda Henley, head of Digital Research Services, at Davis Library (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

In August 2020, the group released the project, called “On the Books: Jim Crow and Algorithms of Resistance,” to the public. Users can search through the laws, download their text files, and view all of the North Carolina statues from 1866 to 1967.

When the Mellon Foundation heard about On the Books, they contacted Henley about expanding it and have since provided additional funding for her team to do so. For the next two years, they will identify Jim Crow Laws within two additional states and will help research and teaching fellows learn how to use these data within their own projects and schools.

It is not unusual for librarians to lead projects of this caliber, Henley shares. While they aren’t considered faculty members at Carolina, librarians undergo an appointment and promotion process similar to tenure and are expected to be involved in professional organizations, publications, and research. For On the Books, Henley and her team wrote a paper outlining the methods and workflows for the project and another that was published in the annual conference proceedings for the Association of College & Research Libraries.

“I’ve found that researchers are more and more cognizant of the amount of input librarians can provide into their research projects and are eager to include them in their acknowledgements, even as coauthors,” she says.

Reviewing Infectious Disease Research at the Health Sciences Library

Imagine wanting to compile all the research that exists on one particular topic. To do so, you collect every academic paper that mentions it and end up with thousands of papers that need to be screened and sorted to find the most relevant papers on said topic. Then, you need to use that information to write a new paper providing a comprehensive overview of all that material.

In a nutshell, that’s what a systematic review is. Health researchers engage in this process often, to not only provide the best recommendations for medicines and practices, but to uncover gaps in the research and improve future work in that area.

Infectious disease researcher Weiming Tang engages often with librarians at the Health Sciences Library whenever conducting a systematic review. Thankfully, the process described above can be completed digitally to find all of the materials necessary to complete a review. Even so, the entire process can take as long as two years.

Most recently, Tang worked with librarian Jennifer Bissram on a systematic review for tuberculosis care and treatment. Bissram starts by creating a search algorithm, which she tests with random papers generated by Tang and his team to make sure it identifies the materials they’re looking for. If the algorithm is unsuccessful, Bissram creates another and tests, repeating this process until she finds one, or more, that works.

Weiming Tang, associate professor of medicine and co-director of UNC Project-China, at Health Sciences Library (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

Once a successful algorithm is created, Bissram uses it across multiple databases, collects the results, and deletes duplicates. This is followed by a screening process to identify whether each paper found meets the criteria for the study. They start by reviewing titles and abstracts, narrow their results, and then complete a full text review, examining the remaining studies in detail. For this particular project, Tang and Bissram whittled 20,000 results down to 250 papers.

After Tang starts writing the review, Bissram will check in to make sure it follows publication guidelines. This ensures a high-quality review with literature-generated evidence that can be duplicated.

“In the past seven years, I think I’ve done at least 10 systematic reviews with Jennifer, and she helped with the whole process,” Tang says. “This is very time-consuming, and she needs to understand exactly what I want from the literature — and she’s not a researcher in my field. She and the Health Sciences Library are a fundamental part of this work.”

Exploring Japanese Prints at the Sloane Art Library

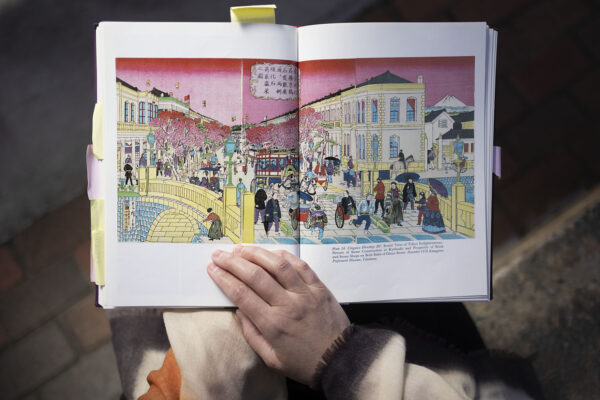

Between 1868 and 1912, Japan experienced a slew of social, political, and cultural shifts that led to the modernization and Westernization of the country. During this time, called the Meiji period, Japanese artists began making inexpensive, colorful woodblock prints showcasing this rapid industrial overhaul — ships entering harbors, trains rolling through newly erected stations, Western fashions like hoop skirts and top hats.

The Ackland Art Museum is home to nearly 500 of these prints, gifted by Gene and Susan Roberts, and is set to become one of the leading repositories for this material in the United States. The prints are being showcased as part of a year-long exhibition within the permanent galleries of the Asian art collection called “Pleasures and Possibilities: Five Patrons of the Ackland Art Collection.” It opened on March 11.

Dana Cowen was tasked with choosing a collection of woodblock prints to display in the show. As the Ackland’s Sheldon Peck Curator for European and American Art before 1950, Cowen wasn’t well-versed in Japanese art — but the prints presented a fascinating topic to explore. To learn more about them and the period in which they were made, she traversed the back halls of the Ackland until she reached a door that led to a manicured courtyard facing a towering wall of glass windows: the Joseph Curtis Sloane Art Library.

Dana Cowen, Sheldon Peck Curator for European and American Art before 1950 at the Ackland Art Museum, at Sloane Art Library (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

Since the art library is home to more than 100,000 volumes of books, films, documentaries, and online resources on art from prehistoric times to the present, Cowen knew she could find what she needed there. UNC’s extensive library system is one of the major factors that drew her to the university in the first place.

“I really needed to do research. I needed to have resources that weren’t available elsewhere, that were harder to come by,” she says. “I knew that UNC has this fabulous collection with multiple libraries and a lending program with area universities. So just the amount of material that I’d have access to was a huge selling point for me moving here.”

Many of the Japanese prints that Cowen works with show the industrialization the country experienced in the late 1800s. This print by Utagawa Hiroshige III shows a shopping area in Tokyo in 1874. (photo by Andrew Russell)

Thanks to library resources and with help from Megan McClory, a PhD student in the history department, Cowen has curated a four-part installation for the next year. Because prints are light-sensitive, Cowen will change them out every three months. Each rotation has its own theme: the first focuses on transportation, the second the Satsuma Revolution of 1877, the third fashion and identity, and the fourth amusements and entertainment.

When she’s not engaged in special projects, Cowen stays busy curating a wide range of art — paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, photographs, and porcelain — for the Peck Collection. She also writes articles on the history and interpretation of various artworks to add to the literature for exhibitions and in journals.

“The more information you have, the better the final product of your research is,” she says. “It’s so important to understand past scholarship about certain topics or artworks to recognize how your viewpoint might differ from others’, to help frame your own evaluations, and to offer fresh perspectives.”

Documenting Durham’s Diet Culture with Wilson Library’s Special Collections

In 2006, 4,000 people traveled to Durham to lose weight at one of three major diet centers, according to an article from ABC News. Durham is still home to the centers referenced in the article — the Rice Diet Program, the Duke Diet and Fitness Center (now called the Duke Lifestyle and Weight Management Center), and the Structure House — and has been known as the “Diet Capital of the World” since the 1980s.

Annie Elledge, a graduate student in the geography department, has been interested in fat studies — an interdisciplinary field that unpacks how fatness is portrayed from social, cultural, historical, and political perspectives — for a long time. While working with her advisor, Betsy Olson, to find a thesis topic, she stumbled upon an article that mentioned the Durham nickname and was immediately curious. To learn more about the city’s diet industry, she spent the summer of 2021 working with librarians Sarah Carrier, Renée Bosman, Taylor de Klerk, and Sarah Morris at Wilson Special Collections Library to uncover its origins.

“They were instrumental in helping me figure out what a project like this could look like because I was so new to archival work and didn’t know where to start,” Elledge says. “They make these Google docs that literally have so many links. Oh, here’s a book, here’s a special collection thing. Just all these resources — more than you could ever imagine. And they talk you through your project.”

Annie Elledge, graduate student in geography, in the Special Collections Reading Room at Wilson Library (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

One of those resources was decades of Durham city directories, these giant brown tomes filled with names and addresses of local businesses. Elledge dug through multiple editions, looking for terms like “reducing salons,” “health spas,” and “health organizations” — what weight-loss facilities used to be called. She compiled that information into a list and used online archives, like the North Carolina Digital Collections and NewsBank, to learn how locals felt about the weight-loss industry at that time.

Today, Elledge has a well-established master’s thesis: the history of Durham’s diet and weight-loss industry from the 1930s to 1980s. She strives to understand how the city and the fat body get produced through anti-fatness and where that happens in the city, from weight loss facilities to diet clinics to restaurants.

“The librarians really go out of their way to help people find information,” Elledge says. “And if they can’t find you the exact answer, they’ll find you as much context as possible to help you figure out your project. They provide this safe space to help you feel comfortable and give you everything you need to do that work.”