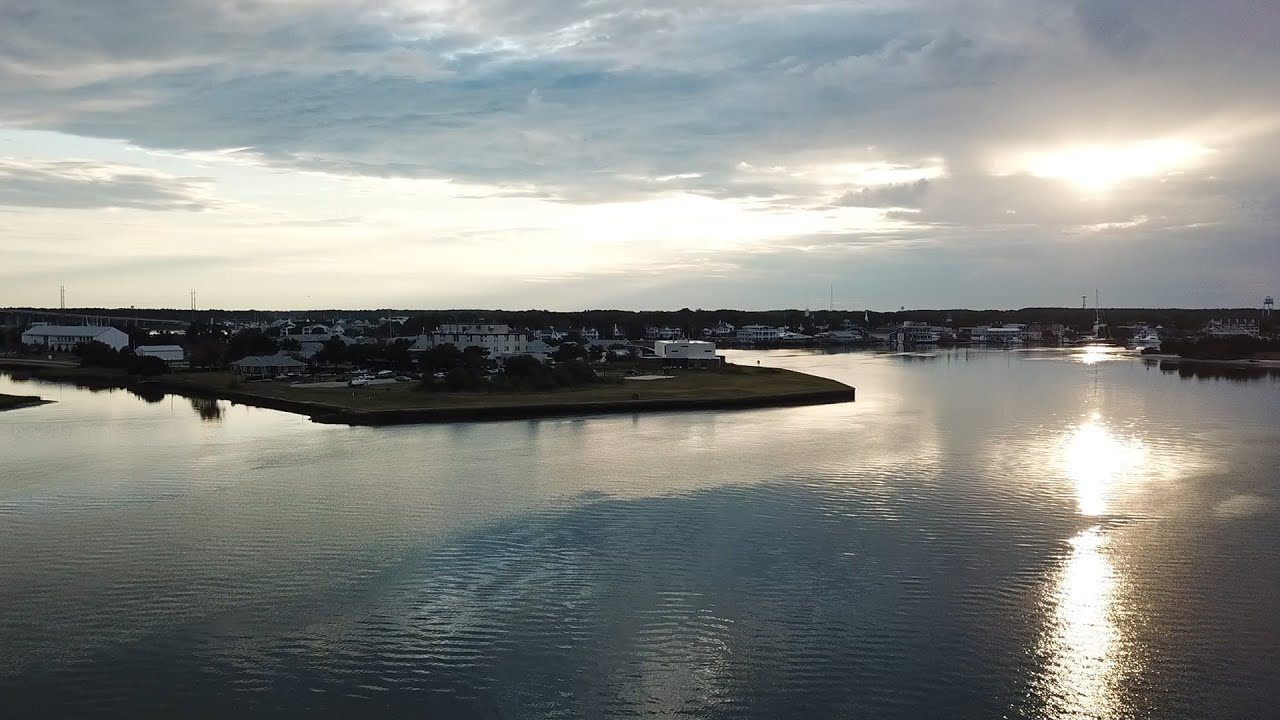

When Todd BenDor, a professor of city and regional planning and director of the Odum Institute, and his fiancé arrived at their friend’s home in Kitty Hawk in 2015 to kick off their wedding week, they received an unexpected greeting. They walked out onto the deck to admire the beach — where they’d have their ceremony in a few days — but there wasn’t one. They peered down to see the ocean licking the stairs that led from the house to the now nonexistent sands, the water undulating with the tide.

Lucky for the BenDors, the wind died down and the water receded a few days later, leaving about 20 feet of sand for them to get married on. Now, each time they return to Kitty Hawk, they find the beach bigger than it was in years past. Each year, expensive beach renourishment projects endeavor to keep the beach in place, with excavators collecting sand from further out in the ocean and spraying it along the coastline, 24 hours a day for months at a time.

Regardless, the beach continues to erode each year.

“It’s like having a dog that bites you and then buying a huge supply of bandages to use whenever he does,” BenDor says. “So, you’re just wearing bandages all the time because your dog bites and bites. It’s treating a symptom and not the actual problem.”

Beaches aren’t the only things that are disappearing. Each year, homes, lives, and entire communities are ravaged by flooding and extreme weather events like hurricanes.

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season broke records on multiple levels. While the season usually runs from June 1 to November 30, the first two storms — Arthur and Bertha — developed in May. Of the 30 storms that formed, 12 became hurricanes, the last of which made landfall in Nicaragua on November 16. This is the most storms on record, surpassing 28 from 2005.

Over 127 million people live in coastal communities in the United States. That’s 40 percent of the nation’s population. What’s more, these communities have a huge impact on the economy, accounting for more than $9 trillion in goods and services.

That’s why BenDor has joined a team of researchers at UNC who are addressing the long-term impacts of extreme events — hurricanes, floods, and forest fires — on North Carolina’s coast from an interdisciplinary perspective.

Led by Carolina Population Center Director Elizabeth Frankenberg, the Dynamics of Extreme Events, People, and Places (DEEPP) project brings together social and natural scientists, engineers, public policy researchers, and data analysts to investigate extreme weather events from all angles, including impacts on health and well-being, economic hardships, and environmental harm. Initial funding for this project came from the Creativity Hubs, a seed-funding program out of the UNC Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research.

Using satellite imagery, geophysical models, and survey data, Frankenberg and her team hope to document the short- and long-term impacts of flood events and how people recover from them to help North Carolinians and other coastal communities prepare for the coming decades — and the storms they’ll continue to face.

Measuring human health impacts

On December 26, 2004, a 9.1 magnitude earthquake struck the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. Within a few hours, tsunami waves as high as 100 feet battered shorelines, killing more than 225,000 people. Countries throughout the region were affected.

In the months after the tsunami struck, Frankenberg and colleagues began studying how it affected communities in Indonesia. They designed a survey to measure the evolution of physical and mental health, as well as economic resources, after the disaster and during the multi-year rebuilding phase. In September 2005, Frankenberg traveled to Indonesia to work with teams on the ground.

Battered homes and debris continued to cover the landscape in Meulaboh, Indonesia, nine months after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. (photo courtesy of Elizabeth Frankenberg)

“Many of the people who survived experienced harrowing events. I remember talking to a woman who made it back to shore after spending 10 hours clinging to a palm tree in the ocean,” she says. “Others watched their family members drown — and could do nothing.”

Frankenberg and her colleagues have collected data from the same individuals multiple times since the tsunami hit. They have documented links between exposure to the tsunami and post-traumatic stress, levels of inflammation, and other indicators of poor cardiovascular health.

“The fingerprints of these events last for a long time,” she says. “Even 15 years after the tsunami, we’re detecting differences in physical health outcomes among those who were living in areas that sustained heavy damage when the waves came ashore compared to those whose homes were in less damaged areas.”

Frankenberg hopes to apply her knowledge from the Indian Ocean tsunami to the East Coast, which experiences multiple storms and flooding each year.

To uncover the impacts of these storms on North Carolinians, Frankenberg is studying how they were affected by Hurricanes Matthew, Florence, and Dorian. Conducted in-person and over the phone, the survey includes questions about damage to property and possessions, disruption to day-to-day life, stress, assistance to and from family and neighbors, and access to recovery programs. Frankenberg and her team hope to continue this work in the coming years to understand the evolution of impact and recovery.

“How will the populations in vulnerable areas change over the next 20 years?” Frankenberg wonders. “One hundred years ago, 50 years ago, people thought of these storms as 20-year occurrences. If that’s no longer the case, how does that shape people’s lives?”

Mapping water on land

Less than one year after the Indian Ocean tsunami devastated Asia, Hurricane Katrina smashed into New Orleans. The Category 5 storm killed more than 1,800 people, left 100,000 homeless, and is still considered one of the costliest natural disasters in U.S. history.

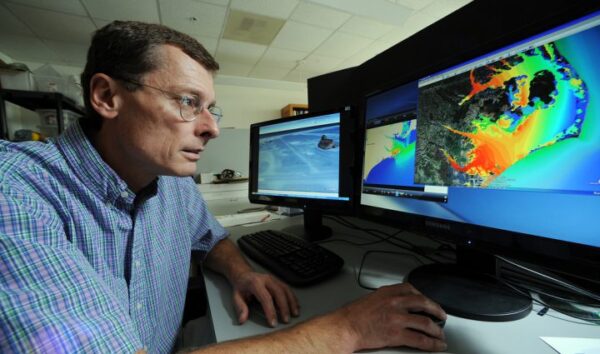

At that time, UNC marine scientist Rick Luettich had been diligently upgrading a storm surge model he co- developed in the 1990s called ADCIRC. Originally created for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to assist with dredging studies, it has since been extensively modified to predict the flooding that will occur on land from coastal waters during extreme weather events.

Rick Luettich co-created the ADCIRC Prediction System, computer models that provide predictions on coastal flooding, winds, and storm surge. (photo by Mary Lide Parker)

Prior to Hurricane Katrina, Luettich and a colleague at Notre Dame University were engaged in a study to apply ADCIRC to model storm surge and flooding scenarios in southern Louisiana. In the immediate aftermath of the storm, limited data made it difficult for investigators to understand the conditions that led to the numerous levee failures and massive flooding in New Orleans. ADCIRC became the primary tool to recreate water levels and flooding from the storm and guided the forensic analysis that followed. ADCIRC was further used to design a new system that provides flood protection for greater New Orleans today.

In the years since Katrina, Luettich has created a forecasting system that uses ADCIRC to predict storm surge and flooding associated with nor’easters and hurricanes that threaten the U.S. coast. Today, ADCIRC can spit out multi-day storm surge forecasts every six hours during active hurricanes. The data produced helps organizations like the U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Federal Emergency Management Agency, and state and local emergency management teams make decisions about evacuations, supply locations, and response personnel.

For the DEEPP project, Luettich is using ADCIRC to recreate recent major hurricanes that have hit coastal North Carolina. The research team will then combine this information with remote sensing data from satellites and airborne sensors to create detailed maps of flooding produced during these storms. This tool will help guide and interpret Frankenberg’s human health surveys and will inform people living in flood prone regions about their vulnerability.

“An active volcano is not going to blow its top every year or even every decade, but eventually something bad is going to happen. In general, people seem to be more cognizant of this danger and tend not to build houses in potential impact areas,” Luettich says. “That doesn’t seem to be the case for people who live in areas that are susceptible to coastal storm surge or flooding. We need to show them what the real threat is.”

Assessing buyouts: another Band-Aid?

Some people who recognize the threat sell their homes to the federal government. Since 1993, the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency has acquired more than 55,000 flood-damaged properties across the nation. Such acquisitions are called floodplain buyouts. While these programs can reduce future disaster relief costs, they aren’t a perfect solution. They can also lower a city’s property tax revenues and accumulate hefty maintenance costs. Like beach renourishment, they may only be a bandage for a much larger problem.

BenDor strives to gather data on these transactions to understand their long-term financial impacts on cities. Most recently, he assessed buyouts in eight North Carolina communities. He and his co-authors found that properties bought at random and in various locations prevent effective land use. If a group of properties in the same area are purchased, though, that land can be converted into public parks or greenways, ultimately boosting the tax base. Most buyouts, unfortunately, end up as vacant mowed lots. Regardless, there is a substantial cost to maintaining them.

BenDor is particularly interested in local governments that permit new construction on floodplains.

“If you look at an aerial photo of Little Washington, North Carolina, it’s like a shotgun blast of buyouts, where the feds went in and purchased the properties,” he says. “And then you have another shotgun blast of new construction on top of it. That’s insane, right? You’re literally spending money to buy people’s properties with the explicit intent of getting them out of harm’s way and then allowing new construction next-door.”

BenDor also studies saltwater intrusion, when saltwater enters freshwater systems after a flood event occurs. This phenomenon can lead to more flooding, ruin drinking water, damage the economy, and affect major parts of an ecosystem, like crop and timber yields, animal life, and natural filtration.

“It can actually create these ghost forests, where the canal system brings floodwater inland far enough that it hits the roots of trees and just fries them,” BenDor says.

To gauge the ecological impact of saltwater intrusion, BenDor is assessing the movement of water across the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula in North Carolina to create a saltwater intrusion vulnerability index. He is also surveying landowners, managers, and other stakeholders to learn about land-use decisions as they relate to saltwater intrusion.

“If the water’s going to be there, especially if it’s saltwater — which is going to damage everything — you gotta get out of the way,” he says.

Observing where the land meets water

After living on North Carolina’s coast for nearly 30 years, Mike Piehler got used to getting out of the way. But he always came back. He recalls the start of the school year in early August, when his kids returned to classes and then would, usually, be sent home a few weeks later when a hurricane hit.

“It was the rhythm of the year. And I’d watch people repeatedly try to get floodwater off their land,” Piehler says. “When I lived there, I sensed a shift where the flooding was more frequent and the water was flowing toward the land more often than it was off the land.”

In fact, when Piehler, a marine scientist, moved to Chapel Hill in 2018 to become director of the UNC Institute for the Environment, winds from Hurricane Florence forced five trees onto the roof of his Morehead City home. Luettich had driven by his property and informed him of the damage — and was, luckily, able to have a tree removal service come and then personally patch Piehler’s roof that same day.

“Florence was absolutely devastating and miraculously turned out not to be catastrophic. But it was still really terrible,” Piehler says.

Piehler continues to study the coastal environment. He researches where land and water intersect, observing how natural and humanmade systems protect coastal towns before, during, and after storm events.

Natural systems like forested wetlands and marshes, oyster and mussel reefs, and seagrass beds often help sustain local ecosystems, stabilize shorelines, and improve water quality. Human-built systems include breakwaters, levees, and stormwater pipes, some of which are more sustainable than others.

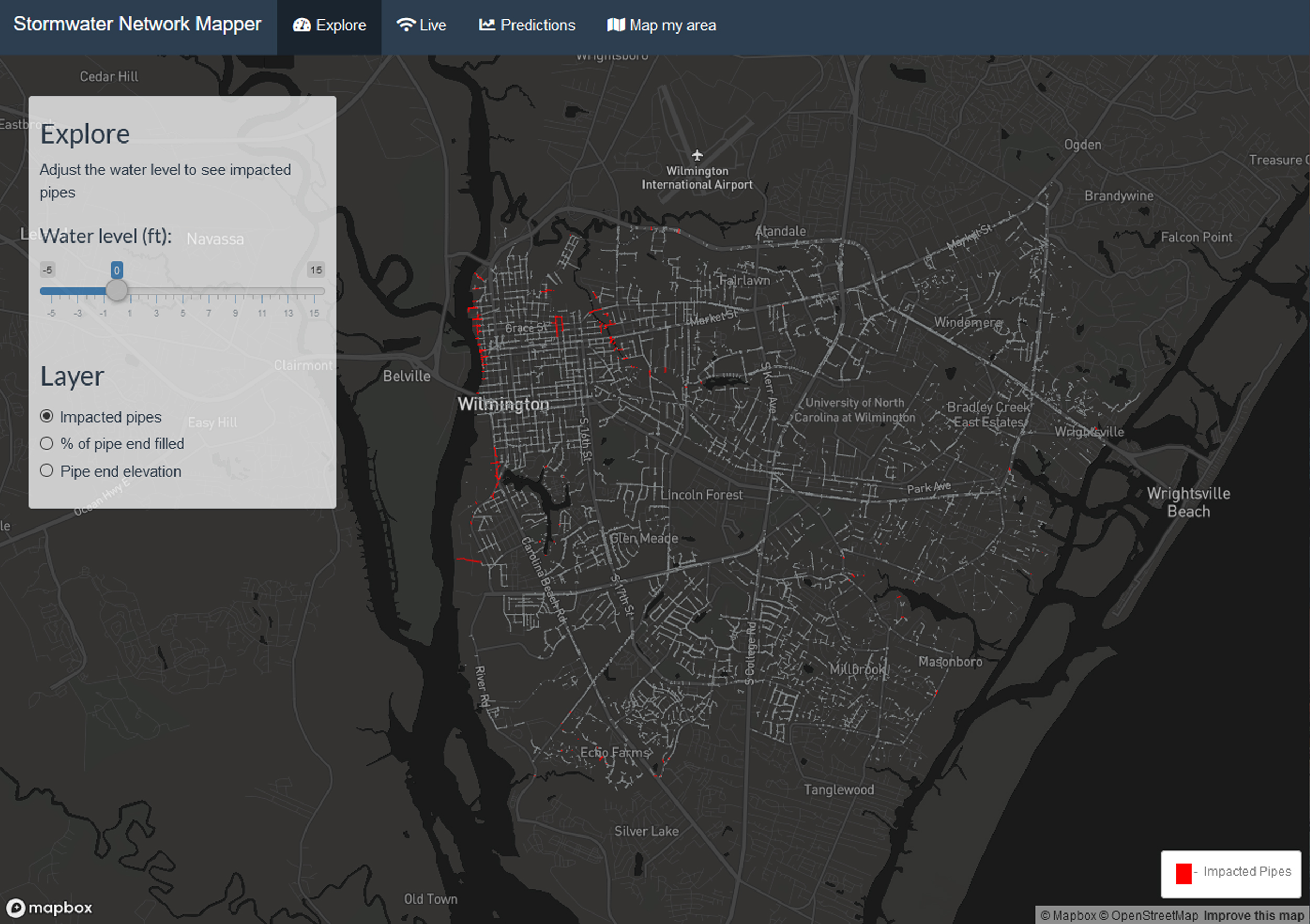

Impacted pipes in Wilmington, North Carolina, appear in red on Adam Gold’s stormwater network mapper. (screenshot from https://gold.shinyapps.io/SW_network_app/)

As part of this work, Piehler’s PhD student Adam Gold has created a stormwater network mapper for Wilmington, North Carolina, that shows all the storm water pipes for the area, highlighting the ones that no longer function.

“Many of us in this group have a first-hand understanding of all of these issues — having either lived or worked on the coast,” Piehler says. “You don’t have to be in the place you’re studying, but you get insights by immersing yourself. We’re not going to sit in Chapel Hill and take a megaphone and tell the coast what to do. We are fully entrenched and engaged in immersive field work.”

Accelerating with team science

Frankenberg, Luettich, BenDor, and Piehler are just a few of many researchers working on this project. Others are researching a variety of topics including how natural disasters affect schools, contaminate water systems, and lead to public policies that mitigate risk. This breadth of expertise is key to developing short- and long-term solutions to climate change, as is the team’s access to a variety of hard-to-get data sets.

“One of the huge problems in hazards research is it’s kind of everyone doing their own thing,” BenDor says. “So when Elizabeth first got us all together, it was like, Wow, you have access to all this data? Or, You know about this type of data? I’ve been really interested in looking into that, but it sounds like you know a lot more. And boom: That’s a huge benefit.”

Thanks to a recent $3.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation, the team is confident their approach is worth pursuing.

“This is confirmation that we’re on the right track,” Frankenberg says. “The NSF grant is the lift to get off the ground. You need that fuel to really climb.”